On the bulletin board someone had posted a crude sketch of an addict injecting himself, along with the caption, “When will it ever end? Never?” Someone else crossed out the “Never” and wrote, “When you dig yourself”.1

In 1965, psychiatrist Marie Nyswander was sitting in a storefront clinic in Harlem with a group of addicts. Some of them were there for help, but others had just come to sit and chat over a cup of coffee.1

One addict said, “I saw that guy Sam on methadone… The cat turned down heroin last week. Free heroin. And he turned it down.” Nyswander nodded and said, “That’s the way it’s worked so far”.1

To reach this point in her career, Marie Nyswander had meandered along a convoluted, sometimes impulsive, path of personal and professional highways and byways. But collectively those paths led her, perhaps inevitably, to that Harlem narcotics clinic and to a discovery that has transformed the way we view and treat opiate addiction.

Mary Becomes Marie

Mary Elizabeth Nyswander was born in 1919 in Reno, NV.1–3 Her father, James Nyswander, was a professor of mathematics. Her parents divorced when she was two years old, and consequently, she was raised mainly by her mother, Dorothy Bird Nyswander.1–3

Dorothy earned her master’s degree in mathematics from the University of Nevada. While teaching high school, she completed a PhD in psychology from UC Berkeley. She then taught advanced statistics, psychology, and public health at various universities and was instrumental in founding the Berkeley School of Public Health.1–3

After retiring from academia, Dorothy spent 16 years with the World Health Organization, traveling widely. In India, she developed education programs on birth control and vaccination, as well as the curricula for new schools of public health.1

Dorothy was fearless and instilled in her daughter the same toughness, intellectual freedom, and devotion to serving others. She also included her daughter in discussions with her friends, anthropologist Margaret Mead and the Gestalt psychologist Max Wertheimer, among others.1,3

When Mary Elizabeth was a teenager, she decided there were too many Marys, so she changed her name to “Marie,” which she thought had more “character”.2,3

In 1933, Marie contracted tuberculosis and spent a year at a sanatorium in Monrovia, Calif. While recuperating, she read widely and nurtured her already independent, progressive views.1,3

Seeking Surgery

In 1936, Dorothy moved to New York City to begin a four-year research project on school health services.3 Marie accompanied her mother and enrolled in Sarah Lawrence College. She was the college’s first pre-med student, and the faculty designed a whole psychology course for her. For courses not in the curriculum, such as physical chemistry, they brought in teachers from other schools.1,2

Marie graduated in 1941 and applied to 20 medical schools. She was accepted to all of them. She chose Cornell University Medical College.1–4 Marie wanted to become a surgeon, but her rotating internship at Meadowbrook Hospital on Long Island also included training in obstetrics, orthopedics, infectious diseases and other specialties.1,2

Marie then sought a naval position, but the U.S. Navy did not take female surgeons.3 Instead, she accepted a commission as a lieutenant (junior grade) in the U.S. Public Health Service, hoping to travel and have an international adventure.1,2 Instead, she was posted to the Public Health Service Hospital in Lexington, KY.1–4

Posting in Public Health

The Lexington facility opened in 1935 as a federal drug rehabilitation hospital and prison. The sprawling hospital complex was surrounded by thousands of acres of farmland and old-growth trees.2

Legislation in 1924 had banned heroin for any purpose and instantly criminalized opiate addiction in the United States. Prisons soon filled up and by the late 1920s, one-third of people in federal prisons were those with drug convictions.2

In response, the federal government established Lexington, a first-of-its-kind facility. About one-third of the addicts came voluntarily for detoxification, but everyone was called a patient, whether they were there voluntarily or not.2

New patients were required to stop using drugs. The medical staff would ease their withdrawal symptoms by tapering the dose of morphine over several weeks. Then, the patients joined the general population for the rest of their stay. There was some individual and group psychotherapy, but mostly, the recovering addicts were kept busy with craft classes, work and recreation.2

Lexington also housed a research clinic, which sought cures for drug addiction. Although informed consent regulations did not yet exist, all of the research subjects were strictly volunteers and were fully briefed on the experimental protocols.2

Some research subjects who had successfully withdrawn from drugs were “re-addicted” and put through withdrawal again.2 The researchers explored drugs that might help ease withdrawal symptoms and evaluated various drugs’ relative addictive power.2

Lexington Experience

Nyswander arrived at Lexington for a medical residency and had no particular interest in addiction. Her assignments included surgery, withdrawal management, therapy, and parole evaluation. She said she didn’t like being responsible for deciding whether another human being should be paroled, so she never said no.1

At 26, Nyswander was single and the only female doctor.2 All of the other doctors were married with families. They branded the addicts as psychopaths, ordered them about, and subjected them to racial slurs.3 Nyswander’s progressive, Northerner manner was foreign and unwelcome. Instead, she developed a rapport with the patients, many of whom treated her kindly.1,2

But the job could be scary.1,2 She was mugged a few times by addicts looking for drugs. When the female patients rioted, the guards sent her to diffuse the situation. Once, she was dispatched to the women’s dormitory, where the curtains and mattresses were ablaze. Trembling with fear, Nyswander bravely walked in, offered the women cigarettes, talked to them, and managed to calm them down, while the guards put out the fire.2

There were many things Nyswander disliked about Lexington, but her most enduring memories were the patients who looked out for her when she was feeling lonely.2 The experience gave her a desire to treat addicts more humanely, rather than as institutionalized criminals.3 By the time she left Lexington, she was no longer interested in surgery. She wanted to learn more about these patients and the pathology of the addiction.1,2

Seeking Psychiatry

When she was discharged from the Public Health Service in 1946, she enrolled in a three-year comprehensive course in psychoanalysis at New York Medical College.1,4 She attended classes at night and served as a resident in psychiatry at Bellevue Hospital during the day. The value of interning at Bellevue, she explained, was that she saw a tremendous number and variety of mental illnesses, and she acquired “a sensitivity for diagnosis”.1

In New York, the standard method for treating addiction was abrupt abstinence, a wrenching and often violent process.4 Whereas, at Lexington, Nyswander had seen addicts withdrawn slowly and carefully. When she faced stern resistance to the Lexington method, a Bellevue colleague encouraged her to publish a paper on her views.1

The paper was a practical guide for doctors with only the resources available in the average hospital.1,5 She described how much morphine to give, how to slowly wean a patient off of it, and how to make sure they didn’t smuggle any drugs into the hospital during withdrawal.5

Private Practice

In 1950, Nyswander set up a private psychiatry practice on Park Avenue. She dealt with a full range of psychiatric problems.1,3,4

Having published her views on drug withdrawal, she thought she could “have nothing more to do with addicts”.1 But she was wrong. The medical literature on opiate addiction was sparce, and her paper marked her as an authority. She received a steady stream of inquiries.6

Nyswander wanted to help, but she had few tools at her disposal. She had been trained in Freudian psychoanalysis, and medical schools did not cover addiction. No one knew much about it, including Freud.6 Still, she felt an obligation to “[handle] the addicts in whatever stumbling way I could”.1

In standard practice, addicted patients were hospitalized during withdrawal. But large metropolitan hospitals, including in New York, refused to admit them.7,8 Most addicts only went to hospitals to get narcotics because their street supply was exhausted, and they left when the lowered doses began triggering withdrawal symptoms. Addicts would also force nurses to open narcotics cabinets.7

It’s Complicated

The first patient Nyswander supervised through a drug withdrawal was an elderly man who had become addicted to morphine following surgery.1 He was too frail to go to the Lexington facility. She dictated a withdrawal schedule to the man’s attending physician, and within 3 weeks the patient was successfully withdrawn. After that, Nyswander oversaw successful withdrawals of hundreds of home-based addicts.1

For addicts who wanted to kick their habit and who had a supportive relative or friend, Nyswander gave the caregivers instructions over the phone.1 Unfortunately, sooner or later, most of these patients relapsed.

In 1951, New York State held a hearing about the addiction problem. Nyswander (now an acknowledged expert) testified about her experiences in Lexington. She was asked, “How many people who went to Lexington recovered?”.2 She said, “I would just say 15%. And that may be very generous, very generous indeed”.2

Lexington’s own figures at the time were closer to 25%, but it was really hard to know. She was asked if there was a specific remedy to treat drug addiction. Nyswander said, “Not that we know of now”.2

Sidney Tartikoff on the panel asked, “I know that you are a very fine practicing psychiatrist. Do you think that psychiatry in and of itself is the answer to the treatment and cure of addicts?” Nyswander said, “No. No. [It’s] far more complicated”.6

Nyswander was asked, “How many people who went to Lexington recovered?” She said, “I would just say 15%. And that may be very generous, very generous indeed.”

Applying Psychoanalysis

In 1955, Nyswander organized her first clinical study.8 She financed this Narcotic Addiction Research Project herself and organized 30 professional psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers as the study team.

They applied the same psychoanalysis procedures that were used to treat other emotionally disturbed patients, and the addicts’ participation was voluntary.8 After a year, only 13 of the 70 patients were withdrawn and still attending psychotherapy sessions. It was a pioneering study, demonstrating that some addicts could be withdrawn as outpatients, but obviously, psychotherapy helped very few of them.8

In parallel with this Research Project, Nyswander wrote a book, The Drug Addict as a Patient, which was published in 1956. It summarized her experiences and views on addiction treatment.1 Although she was still early in her career, Nyswander had tried to rehabilitate more different kinds of addicts than perhaps any other psychiatrist in the country. They ranged from a self-educated homicidal paranoid to a graduate student at MIT. She concluded that everyone had the potential for drug addiction, regardless of intelligence, social status, occupation, religion, or race.1

Quitting is Hard

Despite Nyswander’s psychiatric skills, the low success rate of the Narcotic Addiction Research Project only confirmed the dismal outcomes of all abstinence-based programs.3 Patients, sick of the grind of addiction, would go through withdrawal, cooperate in treatment, and do well for a while.3 Then, eventually, they would meet someone or encounter something that triggered getting a fix. Some addicts would cycle between addiction and detoxification repeatedly.

Nyswander was becoming frustrated.3 She was losing 5–20 patients a year from drug overdoses.1

Her own heavy smoking may have led her to question whether addiction was a psychiatric disorder at all. She started smoking at 14 and by the 1950s was smoking three packs a day.3

Once, she managed to quit for 8 months.7 The craving for cigarettes remained intense. “After six months,” she said, “I still had dreams in which I’d surreptitiously cop a cigarette… If it’s that hard to stop smoking, think what it must be to stop taking a drug like heroin”.7

She concluded that rehabilitation should not deprive addicts of the drugs that stabilized them. “It’s like saying, I’ll treat you for stuttering if you’ll stop stuttering”.1

Nyswander concluded that rehabilitation should not deprive addicts of the drugs that stabilized them.

The Harlem Clinic

In the 1950s and 1960s, organized crime smuggled most of the heroin into New York City. They specifically targeted their sales in Harlem, where more than half of the nation’s narcotic addicts lived, and treatment was largely absent.2,3,9

“There wasn’t anybody [else], and I just said, you can’t abandon them”.6

Around 1961, Nyswander set up her makeshift office in conjunction with the East Harlem Protestant Parish.1,4,6,7 The storefront clinic was on the first floor of a tenement building. The sparce furnishings consisted of a narrow cot, a few chairs, a desk, a filing cabinet, and a single 100-watt lightbulb.7

Each Tuesday and Thursday afternoon, Nyswander offered her “storefront psychiatry” to all comers.6,7 It was unlike her Park Avenue psychiatric practice, where middle-class patients completed their analysis, and typically, never returned.1

In contrast, the Harlem patients, who were mostly young Black or Puerto Rican men, just dropped in. No appointment or payment required.6,7 They sat, had some coffee, and talked to her. And although they were not “cured,” they kept coming back.7

By all accounts, Nyswander was an exceptionally gifted analyst, and her rapport was legendary.3 She adapted to each individual patient. Out of curiosity and compassion, she was able to see the world from their perspective, understand their issues, and establish a deep relationship.1,6 She was never pretentious, judgmental, or demeaning.6

To build that relationship, she did things that she would never consider in her Park Avenue practice. She gave them letters of reference for their jobs and once paid an addict’s rent.7

She was known for her candor, energy, honesty, and sense of humor.4,7 One Puerto Rican patient said, “I can talk to her and blow my top if I want to—and believe me, she can blow her top, too. Or, I can just light up a cigarette and talk about anything. And she’ll never turn her back on you”.7

By 1962, Nyswander had exhausted every psychiatric treatment available: hypnosis, group therapy, and even moving patients to a new environment.3,10 Nothing worked. She began to wonder whether there was a better way.1

Then, Vincent Dole called.

Joining Rockefeller

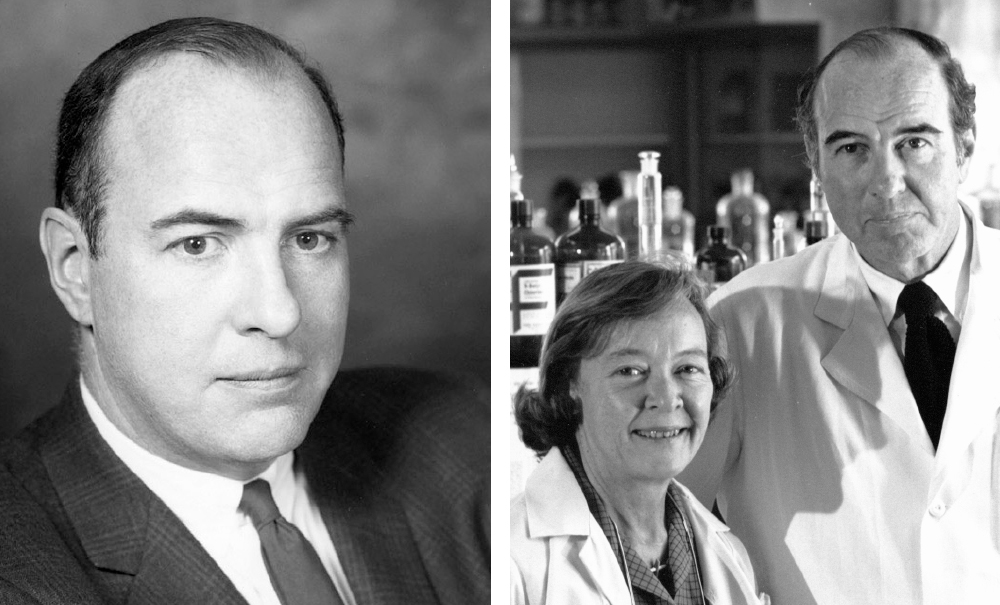

Vincent Dole was born in Chicago in 1913.11,12 He majored in mathematics at Stanford and received his MD from Harvard in 1939. After completing his internship at Massachusetts General Hospital, he joined the Rockefeller Institute in 1941. Dole served as a lieutenant commander during World War II in the Naval Medical Research Unit at Rockefeller’s hospital.11,12

In 1947, Dole was named an associate member of the Rockefeller Institute. When the Institute became Rockefeller University in 1955, he was appointed a professor.12

Dole was an established expert on metabolism, hypertension, and lipid chemistry. In the early 1960s, he became interested in appetite control systems and helped his Manhattan patients lose weight.10,11 Unfortunately, they always returned to their former weight, as though their metabolism had a fixed set-point. He thought, perhaps, differences in metabolic activity explained the food craving and resulting obesity in some people but not others.10,11

In 1962, Lewis Thomas asked Dole to temporarily take his place as chair of the New York City Health Research Council’s Committee on Narcotics, while Thomas was on sabbatical. Dole had no experience with narcotics or drug addiction, but he thought he could handle this largely administrative position.3,10

Even so, Dole wanted to understand the Committee’s work and read everything he could about addiction.3,10 He soon saw a possible connection between metabolism and addiction. Perhaps drug addicts craved narcotics, like obese patients craved food.

Dole was most impressed with Nyswander’s articles and her 1956 book.3,10 He later said, “The only person that made sense to me just as a clinician was Marie Nyswander”.10 In addition to explaining addiction and withdrawal medically, she argued that addiction was a sickness, not a criminal matter, and that punishing people or coercing them to withdraw just didn’t work.10

In October 1963, after a year of exhaustive study, Dole contacted Nyswander.1 They had several conversations, and she impressed him as a very intense, intelligent clinician with a good heart and lots of spirit. He quickly saw her not only as an expert consultant but also as a potential collaborator.1,10

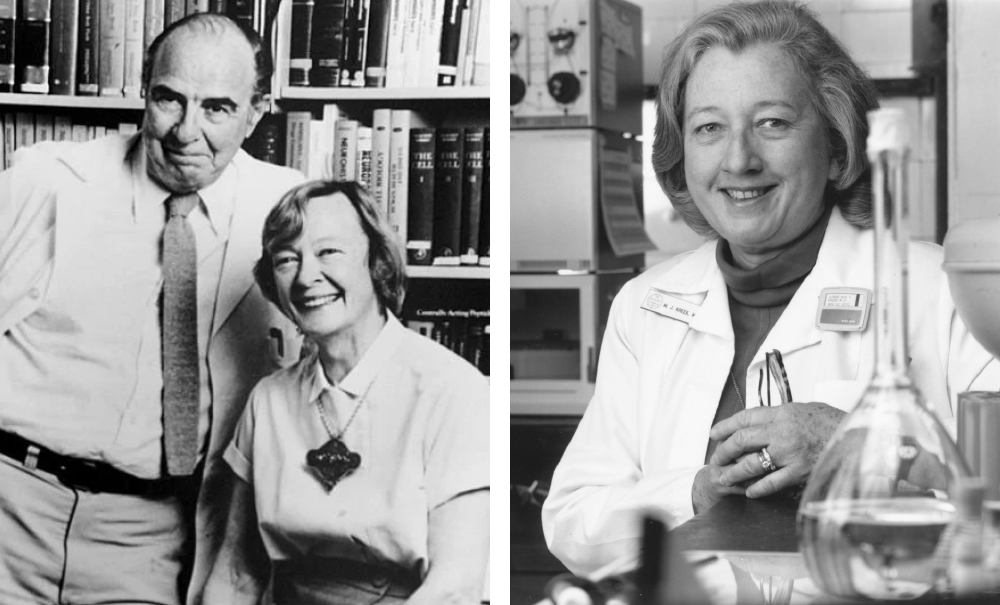

Dole invited her to join his new research project on the biology of addictive diseases.1,4 At the same time, Dole recruited the third member of his team, Mary Jeanne Kreek. Kreek was a second-year resident in internal medicine at Cornell University-New York Hospital Medical Center.13,14 Nyswander and Kreek officially joined Rockefeller in January 1964.3,10

Feeling “Normal”

Their first study was observational, documenting how addicts behaved while taking various narcotics.3 Nyswander served as the psychiatrist, because she had access to the patients and was the most familiar with the behavior and psychology of people with addiction. Kreek observed the patients’ pharmacological responses and monitored side effects. Dole did most of the planning and research design.10

They interviewed hundreds of addicts in hospitals, in treatment centers, and on the street.11 After the interviews, they reconvened and discussed what they had learned.10 Ironically, the addicts said they didn’t like heroin. The initial euphoria was short, and too much heroin made them sleepy. Withdrawal symptoms began when the drug wore off. This cycle repeated 4–6 times a day. In general, the addicts were not seeking to get high. Rather, they said they didn’t feel “normal” without heroin.10

From these observations, Dole concluded that, rather than a psychological condition, some sort of biochemical change made addicts crave drugs. But Dole could not say exactly what that metabolic change was.10

If the problem was a biochemical disruption, then the treatment probably needed to be pharmacological.10 Viewed in this way, abstinence from opiates would never work. Nyswander and Dole often used the analogy of diabetes. Patients with diabetes need insulin, and they cannot be cured by weaning them off of insulin and asking them to live without it.

In general, the addicts were not seeking to get high. Rather, they said they didn’t feel “normal” without heroin.

Elusive Goldilocks

To test this hypothesis, Nyswander and Dole conducted a study aimed at administering a “Goldilocks” dose of narcotics. They wanted to keep the addicts in the “normal” range and avoid the extremes of euphoria and withdrawal.10

They admitted two research subjects to Rockefeller Hospital. One was a man in his 30s, and the other was in his 20s, both addicted to heroin. Nyswander chose the investigational narcotics.10

She tried morphine, Dilaudid (hydromorphone), cough medicine, and even heroin, adjusting the dose and schedule to find the Goldilocks regimen that would keep them comfortable.1,10,15 Unfortunately, nothing worked. The men were comfortable for only 1–2 hours before experiencing withdrawal symptoms.1

Even worse, after several months, the doses were so high and so frequent (day and night) that it was clear this approach was impractical.1,3,10 But Nyswander did make one important discovery. The men were extremely cooperative. They had no desire to seek heroin, because they didn’t need it.1

Nyswander didn’t know what to do next. Then, she remembered a drug that had been used in Lexington.4,10

Buying Ice Cream

Methadone had been developed in Germany by I. G. Farben during World War II as a powerful opioid painkiller to replace morphine.3,10 Because of its long half-life, it produced minimal withdrawal symptoms and no pronounced euphoria. In addition, it prevented euphoria if the addict injected heroin.1,3,16

The Lexington researchers found that methadone satisfied the addicts’ craving and prevented withdrawal.10,11 Unfortunately, some patients seemed to like methadone too much. The researchers worried that patients would surely abuse it and concluded that methadone was too risky. So, they dropped it.10

For her first methadone experiment, Nyswander made a lucky choice. The typical dose of methadone for analgesia was 15–25 mg.10 Because the two men were addicted to high narcotic doses, she administered equivalently high doses of methadone (80, 90, and 100 mg) to ward off harsh withdrawal symptoms.1,10 “What we then discovered,” she said, “might not have been apparent if those dosages had been a lot less”.1

Within a day or two, the men’s behavior markedly changed. Rather than talking endlessly about their drug experiences, they discussed baseball, politics, and other general topics. They were interested in their lives again, including going back to school. Nyswander and Dole had not seen this with any other drug.10

But the two men were living full-time in a controlled hospital environment. The real test would be how they behaved when they went out into the world.

So, they were allowed to leave the hospital during the day. Nyswander waited nervously each night for their return, and they did come back, every night.10 They told her they saw people buying drugs on the street, but they were not tempted. Instead of heroin, they bought ice cream.3,10

The Rockefeller team conducted a series of tests to characterize methadone’s pharmacologic effects.1 The drug could be taken orally, and the only opioid effect the men experienced was constipation.17 Methadone’s half-life was 24 hours, and withdrawal symptoms, which were very mild, developed slowly from 24–36 hours after dosing.1

Under continued methadone use, the younger man got his high school equivalency diploma and went to college and graduate school in aeronautical engineering.1,16

The older man also earned his high school equivalency diploma under methadone maintenance. He became interested in botany, took a two-year course in horticulture, and worked in a greenhouse.1

The addicts told Nyswander they saw people buying drugs on the street, but they were not tempted. Instead of heroin, they bought ice cream.

Methadone Maintenance

Nyswander and Dole wanted to expand their clinical studies, but the 50-bed Rockefeller Hospital was exclusively a research facility, not a treatment center.1 In January 1965, the city’s Hospital Commissioner allowed Dole and Nyswander to occupy an entire floor of the Manhattan General Hospital, which subsequently became the Beth Israel Medical Center.1,3,7,18

They hired a dedicated staff and recruited formerly incarcerated people who were long-term heroin users.1,13

Nyswander and Dole published the results of the first 22 patients in JAMA in August 1965.17 It was, in fact, the first published clinical study demonstrating the scientific rationale and procedures for methadone maintenance.15,17,19 In the series of articles that followed, they expanded their results, reporting the long-term benefit of methadone in hundreds of former addicts.18,20–22 Patients in their treatment program returned to school, obtained jobs, and reconnected with their families.17

Nyswander and Dole advocated a “comprehensive rehabilitation program” which combined methadone administration with supportive social services. They said both components were essential for successful treatment of narcotic addiction.17

In 1966, Dole, Nyswander, and Kreek presented their “metabolic theory” of narcotic addiction and methadone blockade.19 Their data indicated that opiate addiction was a metabolic disorder (now called opioid use disorder) in which addicts’ brains were biochemically and functionally altered.13,14,19 In explaining methadone’s efficacy, they said addicts needed narcotics the same way a diabetic needs insulin.3

This was a major shift from the prevailing view, which classified addiction as criminal behavior or a moral failing.13,14,23 Dole invited the skeptics to visit their ward. Neither the councilmen, hospital administrators, Lexington researchers, nor even Bureau of Narcotics agents could distinguish between the patients (maintained on methadone) and the hospital staff.7,16

Newspapers all over the country published highlights of their results, and Nyswander and Dole gave many interviews. The two investigators became even closer, both professionally and personally. In August 1965, Nyswander went to Tijuana to get a quickie divorce from her third husband and married Dole (his second marriage).16

Nyswander’s work at Rockefeller represented a return to mainstream medicine. She largely put aside psychiatry and embraced the biomedical approach to addiction.3,16 The Methadone Maintenance Research Project was now taking up most of her time, but she continued her schedule at the Narcotics Office in Harlem. And some of those men enrolled in the methadone maintenance program.7

Confirming Efficacy

When Nyswander and Dole expanded their program, they found that addicted patients with an underlying psychopathology (schizophrenia, anxiety, neurosis, etc.) responded less well to methadone. And, not surprisingly, methadone did not benefit those dependent on alcohol, barbiturates, tranquilizers, or amphetamines.20,22

With more than 750 patients successfully maintained on methadone, Nyswander and Dole could boast a 94% success rate in ending the addicts’ criminal activity. Most of those patients became productive members of society. “The results show unequivocally that criminal addicts can be rehabilitated by a well-supervised maintenance program”.18

Still, advocates of abstinence continued to condemn the program on moral grounds. Methadone, they said, simply substituted one addiction for another.3 Nyswander wasn’t concerned that her patients were still taking a narcotic (methadone), because they had become well-adjusted citizens, happy within themselves and socially integrated.1

Despite the critics, methadone maintenance gained ground. By the end of the 1960s, Beth Israel Medical Center had 1,000 patients under treatment.3

The War on Drugs

Because heroin addiction was still a major contributor to crime, President Nixon declared a war on drugs in 1971 and appointed Jerome Jaffe as his “drug czar”.3,24 Federal money was allocated, and Jaffe made methadone maintenance a cornerstone of the national campaign. By October 1973, 80,000 Americans were enrolled in methadone clinics.3,11,16

Unfortunately, as the government’s methadone maintenance program grew, so did the backlash.16 Many communities prohibited methadone clinics, because they didn’t want drug users to be in close contact with their children. They also feared the clinics would attract drug dealers looking for clients.24

Some unscrupulous doctors prescribed large numbers of pills to patients, who then sold the pills on the black market.3,16 The street value of diverted methadone was less than heroin. But for addicts undergoing withdrawal on the street, a diverted methadone dose would tide them over until they could find their next heroin fix.

In response, the Bureau of Narcotics (superseded by the Drug Enforcement Agency in 1973) and FDA jointly imposed restrictions on methadone use.25 The onerous regulations specified who could be treated, for how long, and with what dose, along with stringent clinic security, reporting procedures, staffing requirements, etc.3

Any doctor or pharmacy could prescribe and dispense methadone for pain relief.24 But only physicians and staff (nurse practitioners, physician assistants and counselors) at government-licensed opioid treatment clinics could dispense methadone for addiction.25–27

Patients were required to report to the clinic each day for their oral dose of methadone and underwent frequent urine drug testing. Many patients were forced to travel long distances to reach the nearest clinic, and that was difficult for anyone with a job or children.24

Nyswander strongly criticized those regulations. She thought doctors should decide what medication, including methadone, was best for their patients. For more than a decade, she had given many stabilized patients a one-month supply of methadone, and she had seen no problems.3,16

Overly Optimistic

In 1976, Nyswander and Dole published a 10-year update of their findings.28 Methadone maintenance programs had rehabilitated thousands of former addicts across the country, but they acknowledged that their initial projections had been overly optimistic.

Many heroin addicts remained on the streets and untreated.28 Even stable, well-adjusted patients struggled to find employment. When an employer’s drug tests detected methadone, they would be fired or not hired in the first place. Some patients honestly disclosed that they were in the program but were told the employer did not hire people on methadone.16

Nyswander served on President Carter’s Advisory Board for Mental Health and continued to advocate a holistic approach: a one-stop shop, where patients could get their maintenance drug supplies and assistance with social needs, such as housing, food, and jobs.4,24

A lifetime chain-smoker, Nyswander died in 1986 at the age of 67 after a long battle with cancer.3,4 At that time, methadone maintenance (though widespread and becoming more established) was still controversial. She had freely acknowledged that methadone was not perfect and hoped that better drugs could be found.

Methadone maintenance programs had rehabilitated thousands of former addicts across the country, but Nyswander and Dole acknowledged that their initial projections had been overly optimistic.

Enter: Buprenorphine

In 2002, the FDA approved buprenorphine, which is now the treatment of choice for patients with opioid use disorder.27,29 Buprenorphine is a Schedule III controlled substance and is safer than methadone (a Schedule II drug) because its respiratory depressant effect has a ceiling, and it has a lower abuse potential.24,27,29

The sublingual formulation contains naloxone to deter intravenous and intranasal use. (Sublingual naloxone is poorly absorbed and does not block the systemic effects of buprenorphine.) Maintenance treatment with sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone has been shown to improve treatment retention, reduce mortality, and have a lower abuse potential.27,29

In 2002, the FDA approved buprenorphine, which is now the treatment of choice for patients with opioid use disorder.

New Guidelines

Despite Nyswander’s advocacy, “take-home” methadone was restricted for decades.30 The requirements to qualify included very long treatment times, complete sobriety (based on urinalysis), and evidence of rehabilitation, such as a steady job or a dramatic improvement in the patient’s life.30

Then, in 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, state and federal officials relaxed those requirements, to minimize the risk of COVID-19 infection during clinic visits. Many more patients were permitted to take home up to 28 days of medication. Mobile clinics and telehealth procedures were also established.26,30

Critics were concerned that methadone and buprenorphine would be diverted for illicit use, or that patients would be more prone to overdosing.30 However, a review in The Lancet concluded that despite greater access, methadone misuse and overdosing did not increase.31

In February 2024, the federal government published rules making those changes permanent.26,32 Since April 2024, clinicians have greater freedom to prescribe take-home methadone, which accommodates the patients’ need to attend school, hold a job, and manage their quality of life. The telehealth provision allows providers to treat addiction across the country, especially in rural areas and underserved communities.26,30,32

Dole and Kreek Carry On

After Nyswander’s death, Dole and Kreek continued to study addiction and methadone maintenance at Rockefeller.11,15 Opioid receptors were first identified in 1973, and endogenous opioid peptides were first discovered in 1973. Years earlier, Dole had conceived a lab protocol for their detection and mathematically estimated the number of receptors in the brain.23

Dole always made sure Nyswander’s name came first.30 In 1983, the New York State Division of Substance Abuse Services created the Dole-Nyswander Award, and the couple were the first recipients. In accepting the award, Dole immediately changed the name to the Nyswander-Dole Award, which is still presented annually.4,30

In 1988, Dole received the Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award for the couple’s contributions to managing narcotic addiction as a medical condition.23

In the early 1970s, Mary Jeanne Kreek developed the first lab techniques for measuring methadone and similar drugs in blood and tissues.13,14 Using those methods, she was able to design studies on the physiological effects and safety of methadone. The results were crucial to the FDA’s 1972 approval of methadone maintenance. She also played a role in developing buprenorphine for treating opioid addiction.13,14

In 1985, Kreek was one of the first to document that drugs of abuse significantly alter the expression of specific genes in the brain. She went on to develop animal models for addiction and to identify the biological pathways that act together and make an individual more likely to become an addict.13,14

In the 1990s, Kreek was the first to identify injection drug use as the second major risk behavior (after unprotected sex) for HIV transmission.13,15 HIV infection rates are several-fold lower in methadone-maintained patients than in street intravenous drug users.12,15 Patients taking methadone are also about 60% less likely to die of an opioid overdose.26

In the early 1970s, Mary Jeanne Kreek developed the first lab techniques for measuring methadone and similar drugs in blood and tissues.

Nyswander Street

In 1996, Josh von Soer Clemm von Hohenberg, a Dutch doctor in charge of a drug addiction clinic in Hamburg, Germany, visited Dorothy Bird Nyswander at her home in Berkeley, California.33 He presented her with a gift: a full-sized replica of the large metal sign, “Nyswanderweg,” which marks a residential street in Hamburg.33

Dorothy told an interviewer that naming the Hamburg Street in honor of her only child was “the most beautiful experience of her long life”.3 The replica hung over Dorothy’s bed until her death in 1998 at the age of 104.

Author

-

Rebecca J. Anderson holds a bachelor’s in chemistry from Coe College and earned her doctorate in pharmacology from Georgetown University. She has 25 years of experience in pharmaceutical research and development and now works as a technical writer. Her most recent book is Nevirapine and the Quest to End Pediatric AIDS.

View all posts