This month The Pharmacologist features two new policy briefs written by participants of the 2024 ASPET Washington Fellows program. These topics present compelling arguments for policy improvements on an issue of personal importance to each Fellow. The policy briefs below discuss the importance of understanding polysubstance use and accessible treatments for opioid use disorder in El Paso, Texas.

We Are More Than an Isolated Event: Why Polysubstance Use Needs the Spotlight

By Sarah Melton, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center

Executive Summary

From taking daily maintenance medications, antibiotics, vapes, over-the-counter medications, and pain killers to individuals who struggle with Substance Use Disorder (SUD); people do not administer only one type of medication for their entire life. Nevertheless, why is research conducted like we do? With nearly half of drug overdose deaths involving multiple drugs in 2022 and 250 Americans losing their lives to drugs every day, this is of great importance to Americans at the local, state and federal level.1,2 National public health initiatives are needed to educate the public on polysubstance use as well as destigmatize seeking help for SUD and polysubstance abuse. Additionally, I propose that federal policy makers set up opportunities for polysubstance research to be highlighted within already existing avenues of funding. Finally, Congress should create a committee that focuses on polysubstance use, research, funding, and education.

From taking daily maintenance medications, antibiotics, vapes, over-the-counter medications, and pain killers to individuals who struggle with Substance Use Disorder (SUD); people do not administer only one type of medication for their entire life. Nevertheless, why is research conducted like we do? With nearly half of drug overdose deaths involving multiple drugs in 2022 and 250 Americans losing their lives to drugs every day, this is of great importance to Americans at the local, state and federal level.1,2 National public health initiatives are needed to educate the public on polysubstance use as well as destigmatize seeking help for SUD and polysubstance abuse. Additionally, I propose that federal policy makers set up opportunities for polysubstance research to be highlighted within already existing avenues of funding. Finally, Congress should create a committee that focuses on polysubstance use, research, funding, and education.

Background

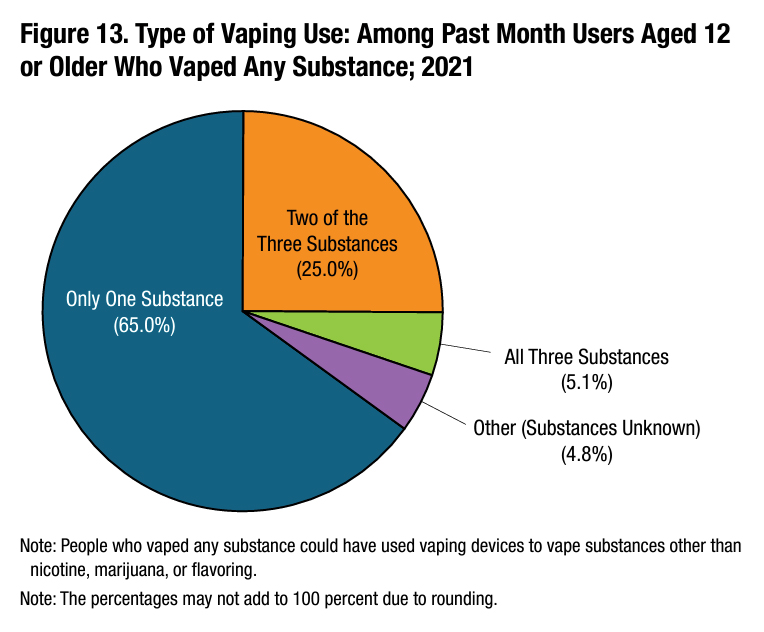

On a personal level, many Americans manage multiple medications throughout their lifetime; often combining over-the-counter medications with other drugs used to treat asthma, high cholesterol, antibiotics and steroids for infections, vaping, birth control, etc…

This polypharmacy extends across various conditions, including post-surgery, chronic diseases, and cancer treatment. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention polysubstance use is defined as, “The use of more than one drug at a time. This includes when two or more are taken together or within a short time period, either intentionally or unintentionally.”2 While genetic influences on prescription drug interactions are studied, little attention is given to the interactions between drugs of abuse, prescribed medications, and over-the-counter drugs. In the healthcare system, most physicians attempt a delicate balance of prescribing multiple medications with a cursory understanding of the downstream side effects. Consequently, there is a large gap in knowledge of polysubstance use from the bench to the bedside. Without proper research and education, the gap widens daily.

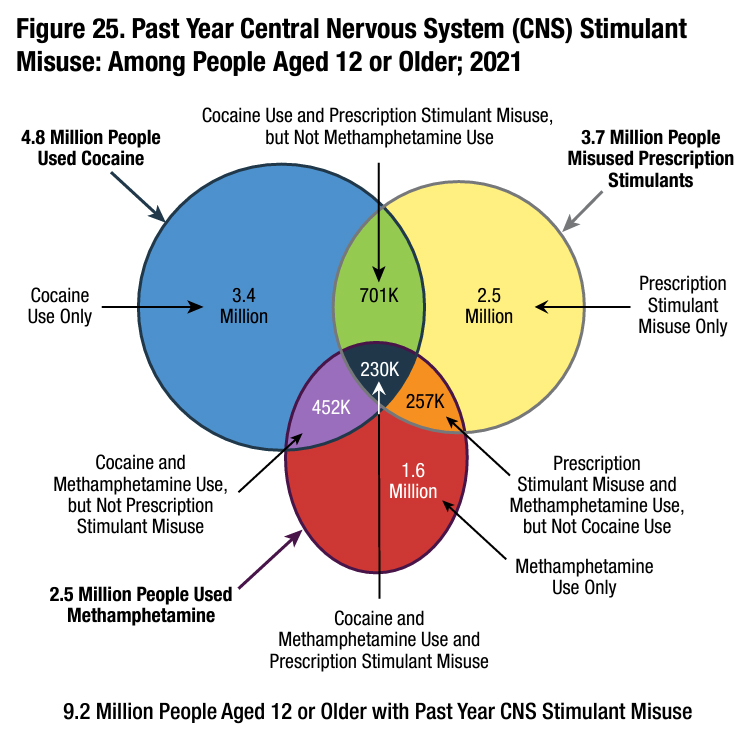

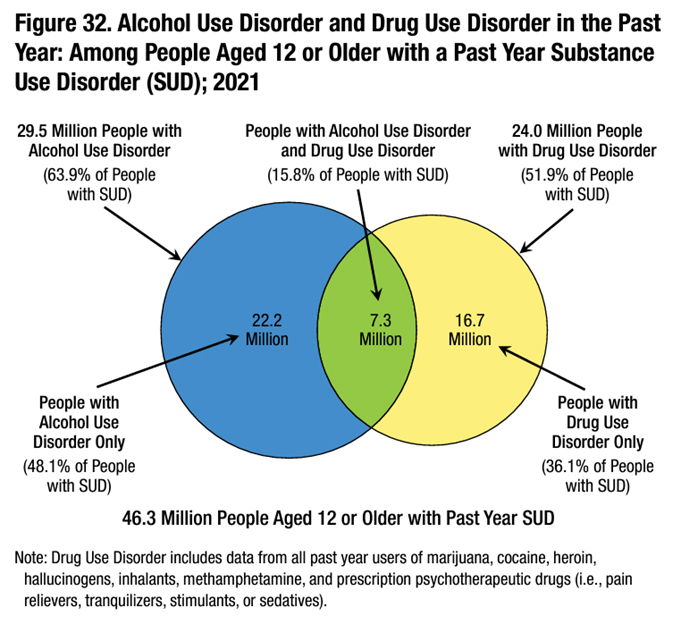

On a national level, while publicly navigating through the COVID-19 pandemic, the silent opioid epidemic persists in the U.S. Drug-related emergency visits reached 7.7 million in 2022, with alcohol, opioids, and cannabis being the most common substances involved.3 Alcohol was the most commonly reported substance in polysubstance-related emergency department visits, often being combined with cannabis, cocaine, and methamphetamine.4 Over 48.7 million Americans experienced a substance use disorder in the past year, with polysubstance use contributing to over 21% of drug-related emergency visits.5 Alcohol and opioids are particularly prevalent, with 16,425 deaths from prescription opioid overdose in 2021 alone.6 According to Crummy and colleagues, polysubstance use is consistently associated with worse treatment outcomes, including poorer treatment retention, higher rates of relapse, and a three times higher risk of mortality compared to using only one substance.7 While steps are being taken to research each type of SUD individually, there is a greater need to study, learn, and treat polysubstance use and polysubstance use disorder.

The current data poorly and superficially addresses the complex web of substances prescribed over an individual’s lifetime, let alone those mixed for recreational purposes. Understanding the interactions between these drugs, their sequence of introduction, and effective treatment strategies is crucial. Substance abuse imposes significant societal costs, affecting consumers, employers, taxpayers, and economic growth. According to the Health Policy Institute:

Everyone pays for the costs of substance abuse. This includes higher prices for goods and services, increased health insurance premiums, and higher taxes for healthcare, law enforcement, and prevention and treatment programs. Substance abuse also diverts resources from future investments and contributes to the need for foster care and homeless shelters.8

To frame SUD in the appropriate context, this is a medical, research, and public health issue.

Instead of focusing solely on restricting access to addictive substances, collaborative efforts across medicine, research, public health, and policy should aim to develop innovative therapies; to expand treatment options, promote harm reduction strategies, and combat stigma through education and evidence-based interventions. This collaborative strategy can reduce the number of emergency department visits and drug overdoses in the U.S., ultimately improving public health outcomes and societal well-being.

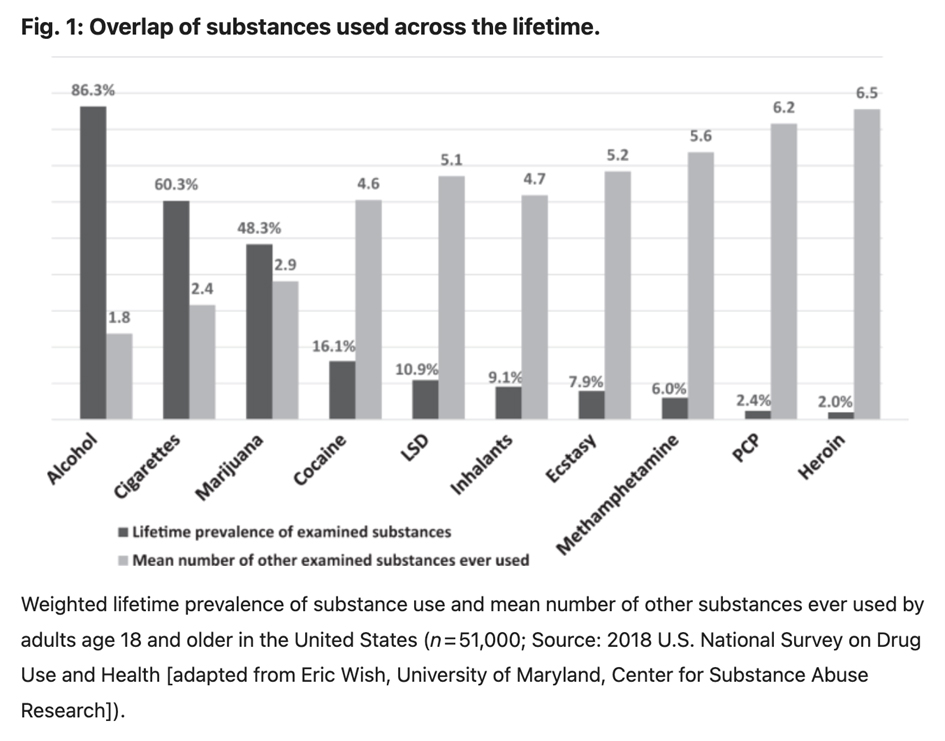

It is imperative to recognize that approximately 92.4% of individuals with lifetime substance use also report lifetime use of alcohol or illicit drugs.9 This statistic underscores the interconnected nature of substance use and the need for comprehensive approaches to treatment and intervention. While efforts to understand and address individual substance use disorders are important, addressing polysubstance use offers a broader perspective on the complexities of addiction and substance misuse. Thus, investing in research and treatment strategies specifically tailored to polysubstance use is essential for mitigating its impact on American public health.

Policy Recommendations

I propose a multifaceted approach to address the pressing and complex issue of polysubstance use and abuse:

- National and state-level public health initiatives are essential to educate the public about polysubstance use. Focusing efforts to destigmatize seeking help for substance use disorder, promote harm reduction strategies, and combat stigma through evidence-based interventions. Through collaborative efforts, we can decrease emergency department visits and drug overdoses in the U.S., thereby enhancing public health outcomes and societal well-being.

- Establish direct funding channels for polysubstance research through already existing federally funded grants. This can be achieved by either creating specialized study sections within existing grant processes or incorporating a dedicated section in grant proposals where researchers can articulate the potential impact of their work on polysubstance use and vice versa. The NIH HEAL initiative or NIDA could spearhead this endeavor to spread across multiple other federal agencies to recognize under-funded research opportunities.

- Create a House of Representatives committee specifically focused on polysubstance research. This committee could operate in conjunction with the Science and Space Technology Committee, providing a structured platform for policymakers to delve into the intricacies of polysubstance issues. With over 56 caucuses touching upon polysubstance use in some capacity, it is evident that this is a pervasive issue requiring dedicated attention and advocacy from top policy makers.

By adopting these measures, we can foster a comprehensive and collaborative approach to addressing polysubstance use; ensuring that research, policymaking, and public awareness efforts are effectively coordinated to relieve the adverse effects of this complex issue.

Accessibility of Treatments for Opioid Use Disorder in El Paso, Texas

By Nina Beltran, The University of Texas at El Paso

Executive Summary

Background

Opioids are a class of drugs naturally derived from the opium poppy plant.1 Opioids can be semisynthetic or synthetic, as they are made in a laboratory. Prescription opioids, such as morphine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone, are prescribed to treat pain-related conditions.2 These drugs act on the brain reward pathway, producing euphoria.2 Taking these drugs chronically to treat pain-related conditions or to achieve euphoria can be problematic, as this increases the risk of drug misuse and can lead to opioid use disorder.3 Opioid use disorder is characterized by symptoms such as taking larger amounts of drug over a longer period than intended, craving or a desire to use opioids, the need to increase the amount of drug to achieve a desired effect, or experiencing withdrawal symptoms from opioids.4 While opioid withdrawal is not fatal, it does cause side effects that create a significant motivation to continue opioid use to prevent withdrawal.5

A recent national survey reported that nearly 2.5 million individuals in the U.S. have opioid use disorder.6 Further, opioids contributed to nearly 75% of all drug overdose deaths in 2020. In just one year, in 2021, this number jumped to nearly 87% of drug-related mortalities.4 Treatments are available for opioid use disorder; however, only 1 in 5 people with opioid use disorder receive treatment. This can include counseling, behavioral therapies, and medication treatment.7 These medications include methadone, which reduces cravings but is only available in regulated clinics. Buprenorphine is prescribed as a replacement for opioids. In addition, naloxone, also known as Narcan, is used in emergencies to reverse opioid overdose when a person is experiencing respiratory depression.8 While these treatments exist, treatment works best when personalized and accessible to the individual.

Individuals seeking treatments may experience barriers or a lack of accessibility. This can include the absence of health insurance in the limited number of facilities offering treatment services.9 Further, certain populations are reported to be less likely to receive treatment, which includes black adults, women, and unemployed individuals.6 However, in March of 2023, the FDA approved Narcan, a nasal spray, for purchase over the counter and approved for use without a prescription.10 While this may be accessible to some, it may not be accessible to all. To fill this gap, harm reduction offers an opportunity to reach people who may not have access to or cannot afford this care. Examples include syringe services programs or syringe exchange programs that provide access to sterile needles and syringes, facilitate safe disposal of used syringes, and provide referrals for treatment programs.11

El Paso, Texas, has a population of nearly 700,000, of which 81% is Hispanic.12 In El Paso, Texas, there are no syringe service programs; in all of Texas, only one program is available located over 500 miles away in San Antonio, Texas.13,14 In 2021, there was a 50% increase in opioid-related mortalities in El Paso, Texas, resulting in 101 fentanyl-related deaths.15 First responders, such as police officers in El Paso, Texas, are not required to carry the lifesaving reversal drug Narcan.16,17 Research supports that increasing someone’s chance of surviving an overdose, the sooner Narcan should be administered.18 Making Narcan accessible to people in the community and first responders is critical to improving outcomes. Specifically, in other states, it has been reported that police officers carrying Narcan results in a reduction in overdose deaths.19 These findings indicate the effectiveness of these practices in mitigating opioid overdoses. There is currently one non-profit organization in El Paso, Texas, known as Punto de Partida, that provides harm reduction resources such as fentanyl test strips, Narcan, and hygiene kits.20 While this organization provides beneficial resources, the stigma of addiction is highly prevalent among Hispanic populations21, which may contribute to the lack of treatment accessibility and barriers to training resources in the community.

Texas policymakers should allocate funding for the service programs located in San Antonio, Texas, to allow expansions of other programs in Texas, including El Paso, Texas. This expansion should include programs targeting education to decrease the stigma and discrimination of drug use. Further, these programs should include resources such as safe disposal of used syringes, fentanyl test strips, and Narcan distribution to minimize self-harm and improve recovery to mitigate existing barriers to treatment and other resources. In addition, Texas policymakers should require first responders, including police officers, to carry and have training on lifesaving reversal drugs, such as Narcan. While emergency medical services (EMS) typically fulfill this role, if police officers respond and arrive at an emergency before EMS, they should have the training and the resources to treat opioid overdoses with Narcan. While treatments for opioid use disorder are accessible to some, this is not accessible to all, especially to those in case of an emergency in El Paso, Texas.