This month The Pharmacologist features two new policy briefs written by participants of the 2024 ASPET Washington Fellows program. These topics present compelling arguments for policy improvements on an issue of personal importance to each Fellow. The policy briefs below discuss the need for more stringent policies on plastic pollution and establishing stronger policy guidelines that help with pain management for women.

Tackling Plastic Pollution: Prioritizing R&D, Global Treaty, and Transparency for Effective Policies

By Kalyanasundar Balasubramanian, PhD, The Ohio State University

Executive Summary

Plastic pollution poses a grave threat to human health and the environment, with 11 million tons entering oceans annually.1 Despite its widespread use, less than 6% of plastic chemicals are regulated globally, contributing to many hazards.2 Current initiatives, such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Circular Economy objectives, aim to mitigate plastic pollution.3 However, urgent action is needed. Our recommendation to Congress is to allocate funding to bolster EPA and NIH environmental sciences groups and advocate for global treaties to regulate plastic pollution and increase transparency in chemical usage. This approach enables science-based policy decisions, ensures accountability, and protects public health and the environment.

Plastic pollution poses a grave threat to human health and the environment, with 11 million tons entering oceans annually.1 Despite its widespread use, less than 6% of plastic chemicals are regulated globally, contributing to many hazards.2 Current initiatives, such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Circular Economy objectives, aim to mitigate plastic pollution.3 However, urgent action is needed. Our recommendation to Congress is to allocate funding to bolster EPA and NIH environmental sciences groups and advocate for global treaties to regulate plastic pollution and increase transparency in chemical usage. This approach enables science-based policy decisions, ensures accountability, and protects public health and the environment.

Background: Understanding the Plastic Pollution Crisis

Plastic is ubiquitous, yet its convenience bears significant environmental and health risks. Plastic pollution stems from its intricate composition comprising over 16,000 chemicals, including basic polymers, solvents, and additives. These additives, such as plasticizers, flame retardants, stabilizers, and pigments, are vital for delivering specific material functionalities. Alarmingly, nearly 4,000 of these chemicals are recognized as hazardous, yet less than 6% are subjected to regulation globally.2,4

The exponential growth of the plastic industry further exacerbates the crisis, with production skyrocketing from 2 million tons in 1950 to a staggering 348 million tons in 2017. Currently valued at $522 billion, the plastic industry is projected to double its capacity by 2040.5 However, this economic boom comes at a severe cost to human health and the environment. Human health effects, greenhouse gas emissions, and marine species endangerment underscore the gravity of the situation.

Exposure to plastics poses significant risks to human health, potentially impacting fertility, hormonal balance, metabolic function, and neurological activity.2 In 2018 alone, healthcare costs linked to plastic chemicals in the United States amounted to a staggering $249 billion.6 Additionally, plastic production contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, with projections indicating that, by 2050, these emissions will hinder efforts to limit global warming to 1.5 °C.2

The consequences of plastic pollution extend far beyond human health, with more than 800 marine and coastal species affected by ingestion, entanglement, and other dangers.7 This ecological impact threatens biodiversity and disrupts fragile ecosystems, underscoring the urgent need for decisive action to combat plastic pollution.

Problem and Current Initiatives

- Plastic pollution is a global crisis with significant economic, environmental, and public health implications.

- Plastic pollution presents multifaceted challenges, including chemical complexity, data gaps, and unregulated hazardous chemicals.

- The unchecked proliferation of plastic chemicals exacerbates the problem, with over 60% lacking essential information on usage and presence.

While the U.S. EPA’s Circular Economy objectives aim to address pollution reduction and post-use management, gaps remain in governance and circularity. Urgent action is needed to fill these data gaps, enact a strong global plastics treaty, and enforce transparent plastic chemical management.

Policy Recommendations

As one of the world’s leading users and generators of plastic, the U.S. has a critical role to play in reducing plastic pollution and protecting our environment, climate, and health.

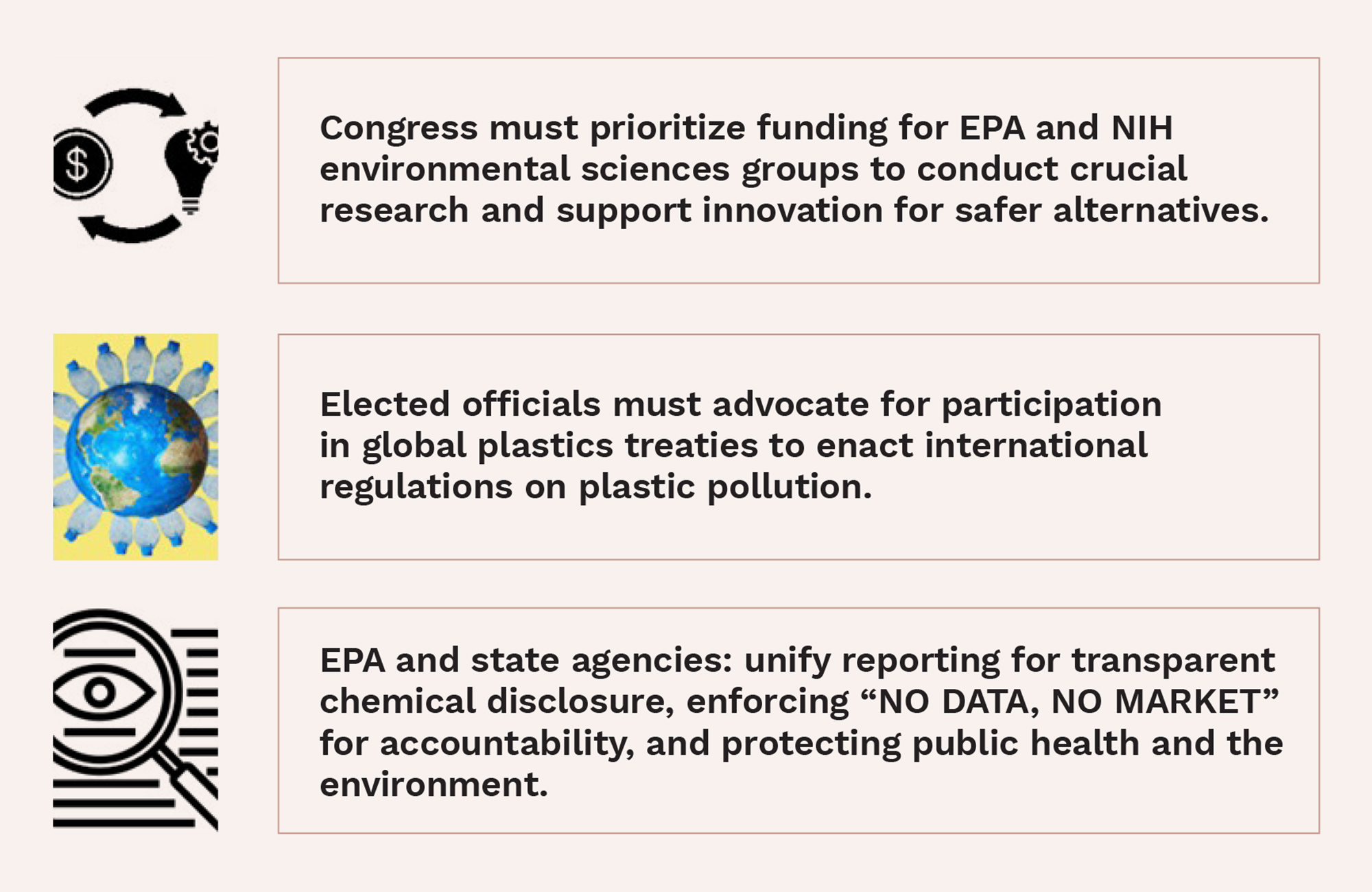

- Strengthening EPA and NIH Environmental Sciences Groups: Our recommendation to Congress is to allocate increased funding to enhance research capabilities and support innovation for safer alternatives.

- Implementation: Funding can be sourced through federal appropriations or public-private partnerships. Specifically, funds should be allocated to establish dedicated research programs focusing on developing safer plastic alternatives, improving recycling technologies, and studying the health impacts of plastic chemicals. Partnerships with academic institutions and private sector innovators will be essential for leveraging expertise and resources.

- Impact: Economic benefits include job creation and innovation in sustainable technologies. Politically, emphasizing public health and environmental protection may garner bipartisan support.

- Advocating for Global Plastics Treaties and Regulatory Reform: Elected officials advocating for global plastic treaties by engaging in international negotiations to establish binding agreements on plastic pollution control.

- Implementation: Lobbying efforts and diplomatic negotiations can secure commitments from other nations. Precedents like the Montreal Protocol can serve as a roadmap. Examining the European Commission’s plastic strategy offers valuable insights. Adopting these established methods in regulatory bodies and international forums will make the proposal more actionable.

- Impact: Globally coordinated efforts can yield significant reductions in plastic pollution and streamline regulatory frameworks. However, political challenges and resistance from industry stakeholders may impede progress.

- Enforcing Transparency and Accountability Measures: The EPA and state agencies implement a unified reporting platform for transparent plastic chemical management.

- Implementation: Legislative action can mandate reporting requirements and enforcement mechanisms. Before any legislative mandates, an interagency working group should establish a report on gaps in agency transparency and accountability and recommend a comprehensive reporting system. For example, California’s Senate Bill (SB) 502 requires manufacturers to provide detailed information on product ingredients and usage, with suppliers stepping in if necessary. Non-compliance results in significant penalties, ensuring transparency. This model can be adapted federally to ensure comprehensive information on plastic chemicals.

- Impact: Enhanced transparency fosters consumer trust and facilitates informed decision-making. However, compliance costs and resistance from industry lobbyists may pose challenges.

Take Action

Plastic pollution poses risks to human health, including infertility and cancer, while also causing severe harm and death in wildlife, alongside contributing to climate change.

Pain Management in Women’s Healthcare

By Shwetal Talele, University of California, Irvine

Executive Summary

- Increasing collaborative research between clinicians and scientists,

- Improving pain reporting techniques and creating a database of pain management options and;

- Improving training curriculum to include diverse perspectives.

Implementing these policies would lead to increased trust, credibility and understanding of women’s pain. It would also result in standardization of pain reporting and allow women to advocate for better care.

Background

Women’s pain is often dismissed by healthcare providers due to an inherent bias that women’s pain is more psychological, insinuating that their pain is a result of their emotions and not real. These cases are more prominent in women of color due to the stereotype that they have a higher pain tolerance.1 However, there is evidence that women feel pain differently than men. Women suffer more from chronic pain in terms of severity and frequency of symptoms such as migraine, arthritis and fibromyalgia. Women also suffer from female-specific conditions such as endometriosis, an inflammatory disease that causes pain in the reproductive system, urinary tract, and digestive system.2

Studies show that the bias against women’s pain translates in the care they receive:3,4,5

- Females wait 29% longer to be seen than their male counterparts in emergency departments.

- Women’s symptoms are twice as likely than men’s to be misdiagnosed as mental illnesses and prescribed sedatives in place of pain medications.

- Women are less likely to have a complete medical assessment, and their pain is often attributed to menstrual cycle.

- Women are not administered pain medications during invasive procedures such as IUD insertions or pap smears and are often made to believe that their pain is only psychological.

Many differences in providing care are because women’s pain is thought to be uncredible. Where men’s pain is validated and they are seen as stoic, women’s pain is often invalidated, and they are seen as hysterical and emotional.6 It has been reported that undiagnosed pain leads to increased depression and anxiety. It affects their productivity, interpersonal relationships, and quality of life. Not providing pain management options during invasive procedures leads to them feeling violated and insecure to seek diagnosis and the care that they need. Additionally, articles report that years of undiagnosed pain has led to late-stage diagnosis of life-threatening conditions such as heart failure, cancer or endometriosis which limits their treatment options and survival.

The bias and inadequate treatment stems from a very subjective pain reporting method, a lack of research on pain in women and lack of appropriate education and training. Currently, pain is reported by rating it from 1–10 by the patient. The severity of the pain based on this rating can be interpreted differently by the healthcare provider, giving room for bias to foster.7 Further, we need more research on pain in women to understand the gender specific differences which influence pain and understand how to alter existing pain management options to account for these differences. Finally, a study done on the curriculum of medical schools indicates that very little training is provided with respect to gender specific care, which does not equip the physicians and nurses to tailor care appropriately.8

Policy Recommendations

Policy recommendations can be made towards the medical boards such as American Medical Association and the Association of American Medical Colleges which certify medical schools:

- Increased translational research allowing clinicians and scientists to collaborate can lead to understanding pain presentation in women, develop strategies to successfully diagnose underlying conditions, and implement interventions to alleviate pain.

- Standardization of pain reporting and creation of database to store information on the pain reported, the treatment given and diagnosis including gender and age without compromising patient confidentiality. A study in 2012 explores the possibility of such a database including information that would

be useful to collect.9 - Improvement in the training curriculum to include increased focus on gender specific differences in pain presentation, severity,

and complexity. - Increased diversity of physicians and nurses to shed perspective on pain management options and improve trust of underrepresented populations in healthcare.

Conclusion

Recently, numerous articles and advocacy groups have highlighted the disparities between genders in pain management which raises hopes that change is possible.1,10 However, there is still a long way to go. The above policy recommendations are targeted towards making efforts to eliminate bias by increasing awareness and understanding. However, these are long-term solutions will take time to be implemented and for the results to be observed. Standardizing pain reporting and creating a database would probably have the least problems as it is easy, it stores large amounts of data that can be made readily available, and it can be modeled off multiple other databases maintained by medical boards and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Finally, creating a database would directly fuel into encouraging translational research allowing us to increase our knowledge base.